- Home

- Stevan Allred

The Alehouse at the End of the World Page 2

The Alehouse at the End of the World Read online

Page 2

The fisherman went into his shack to sleep.

Best enjoy this respite, the frigate bird thought, while it lasts.

§

The fisherman woke well before first light. He hung the leather pouch that held his flint and steel off his belt. He took the letter from his beloved and folded it smaller and smaller until it fit into the leather pouch. The pitch bundles were threaded on the silver chain round his neck. He put on his broad-brimmed hat, and he walked down the path to the cove. The sail was rigged but he left it furled. The sea was calm. He pushed the skiff into the cove and settled himself between the oars. He put the oars in the water and pulled, and he felt the strength of the muscles in his shoulders, and it was good.

Now he was on the open sea, well past the break of the waves on the reef, rowing from swell to swell. The moon was already set, and the stars were bright in the sky. The wind was out of the southeast, and the fisherman shipped his oars. He raised the sail, and his spirit rose as it always did when the wind filled the sail, and his faithful skiff pulled forward. There was phosphorescence in his wake.

He rowed until the sun came up, and he kept on rowing until his shoulders and arms felt like lead. The wind was shifting. He rested himself, drank water from his goatskin, and he chewed down some dried fish. The cove where he lived was behind him, and well below the horizon now. The sun was high enough in the sky that he could see down into the water a fathom or two. Jellyfish floated by in silvery outline against the dark water, their undulant bodies cupping and swelling.

If he were fishing he would let out the sheet line and turn the skiff northward, taking advantage of the current. But he was not fishing, and he kept the sail steady, and he rowed with the wind behind him, cutting across the current. His only course was to sail west until he could sail no longer. To reach the Isle of the Dead, he reasoned, he must be ready to die.

Above him a frigate bird rode the wind. He had seen them, as all sailors had seen them, a week’s sail from land, and he knew them to be stouthearted voyagers. They were riding the wind together, the fisherman on his skiff and the frigate bird, its long narrow wings spread wide, gliding on the winds aloft. Together the wings and the slender black body made the sign of a cross against the sky. It seemed uncommonly large.

Ahead of them, the sky slowly darkened to a gray the color of a shark’s back. A storm was coming, and soon he would take down the sail, lest it be torn from his mast. He kept on rowing, straight ahead, into the wind.

§

When the storm broke over him rough swells sloshed water into the skiff. The waves grew taller and taller, and the wind ripped white foam from their tops. He pulled on the oars with all his strength. If the storm was bringing death to him, so be it. It was what he was here for. Death would come for him and carry him to his beloved. There was no use in thinking of anything more than that. He rowed.

The sky was as black as a pirate’s heart. Raindrops the size of hummingbird eggs pelted him, and he opened his mouth and drank them in. Thunder shook the air so close and so hard his ribs rumbled. Bolts of lightning forked, and forked again. The rain now a torrent, his skiff filling with it, the water soon over his feet. He shipped the oars, and he bailed water with the bucket he kept stowed in the stern. The wind ripped his hat off, breaking the leather cord that held it on his head. The skiff was sideways now, and it rose up the face of the next wave only to tip back on itself, heaving the fisherman into the storm.

He hit the water face-first. An oar plunged into the sea next to him, and he grabbed for it but missed. When his head broke the surface again, his skiff was already out of sight. He rode the next swell, and in a flash of lightning he saw it, his skiff upside down, and already too far away to reach. He was doomed, but he would die a sailor’s death. The swell broke over his head, and he swam downward. He would slip this skin off his rack of bones and let loose his soul that it might fly to the Isle of the Dead.

He was fathoms beneath the surface when a great dark shape came at him. It was moving fast. A predatory eye as big as a barrelhead looked him over and blinked once. Then the whale was upon him. The cavernous mouth opened, and a mighty inhalation of water sucked him in. The jaws shut, and he was squashed against the roof of the mouth by a great slab of tongue. He was pulled farther in, down the throat, the passageway narrowing and slimy.

His arms were pinned to his sides. A flap of flesh as big as a devil ray opened, and he was forced headfirst through a tight slit. He coughed, his lungs wild for air. He opened his mouth expecting only to suffocate, but there was air to breathe. It smelled of cuttlefish and kelp.

He was in the belly of the beast. When he pushed against the walls of the gut they stretched. He lay his head against the wall, and he heard a sound like a huge bellows filling with air. His skin prickled. He’d been swallowed alive. His knife was gone, he knew not when nor where. He touched the silver chain round his neck. If only the whale had bitten him in two instead of swallowing him whole.

He could breathe, but the heat was terrible. It seemed to open his pores and draw out all his vitality, and the fisherman’s body sank slowly down the sloping wall of flesh. He was overcome by a weariness he could not resist, and so he slept.

§

The fisherman thought it should be dark inside the belly of the whale, but the light was red. Tiny bits of phosphorescence glowed around him on the walls of the gut. Above him he heard the steady throb of the whale’s great heart, beating.

There was a story old sailors told about a monstrous whale who swallowed men whole. It was a story he’d never believed, until now.

§

The burning on his skin and the terrible heat made the passage of time tediously slow, but the fisherman had no way to mark it into watch hours, even less so into night or day. There was little to do, but the gut had crevices along its length, and his hands found fish bones and cuttlebones in those folds of flesh. And something more. In one crevice, beneath a small pile of cuttlebones, he felt something round and leathery, and he worked it out of the crevice. It was a leather pouch, and the something round inside it had a handle. He drew it out of the pouch and held it up in front of his eyes. It was a magician’s glass, a device for making the very small appear larger than it was. A rare find, although not of much use to him now. The leather pouch was worn but intact, and he hung the glass in its pouch off his belt, next to his flint and steel.

§

His tongue was swollen in his mouth. He was growing weaker, he could feel that, and his thirst was a patch of desert scree that started with his chapped lips and ran all the way down his throat. He tried sucking some moisture out of the slime all around him, but that only made his tongue swell more. When he slept he lacked the strength to even dream. His mind was wandering away from its moorings.

He was in the belly of the whale, that much he still knew. How many times he had passed back and forth through the curtain of sleep he could not tell. At times he heard a keening sound through the wall of gut around him, a high-pitched, unworldly song that was beautiful nonetheless.

As he fell from wakefulness one last time he knew, dimly, that this was no longer sleep, that he was passing into the dark dementia that would lead to his own demise.

§

When the fisherman woke next he was on his back. His swollen tongue protruded from his lips. He was crazed with thirst, and in his delirium, he saw a pelican’s bill above his face, with a drop of blood hanging from the tip. The pelican looked at him with one yellow eye, taking him in with all the intelligence of an apothecary. The drop of blood let go, and it fell and fell and fell while the pelican regarded him, his yellow eye inhumanly round but somehow compassionate. I am crazed, the fisherman thought, I am washed ashore at the gate to Bedlam. The drop of blood fell onto his tongue. It lay sweetly there. A musty scent like myrrh teased through him, and a tiny pulsation spread across his tongue. The pelican’s yellow eye winked from side to side.

More of the world’s bewitchery. It was enough to make hi

m pass out again.

§

When he woke next the fisherman squinted into a bright but overcast sky above him. The sun was directly overhead. He was on a beach, and waves were lapping over his legs. A cuttlefish beak was in his hand. He was enormously tired, but his tongue was back to its normal size, and he was no longer thirsty. He lay there a long time, listening to the cluck and clatter of birds he could not see. They were behind him somewhere, having a long conversation. At long last he felt enough strength to roll himself over on his side, and then to sit up. The bird sounds behind him stopped for a moment, and then resumed, louder and more upset than before. The sea was green. He was on an inlet, long and narrow, with rocky cliffs topped by fir trees. Giant fir trees, the like of which he had never seen before, not even in the fjords of the northern seas.

His legs, below his knee breeches, were as white as an orca’s belly, as were his forearms, his hands, his belly, his feet. He had lived every day of his life outdoors, and his skin had long since been tanned to the color of almonds. Yet here he was, an albino, washed up on a beach. He rubbed his eyes, which changed nothing, and then he closed them for a dozen slow breaths, but when he looked again, he was still bleached white. Had his eyes been magicked? He could not tell. He had been swallowed whole by a whale, had he not, and lived in the belly for days. Explanation enough for any number of strange things, he supposed, although it did not answer the question of how he had come to be here. He was on no coastline he knew. He had no memory of leaving the whale’s belly.

The bird sounds were getting closer. The fisherman turned over onto his knees and stood his weary body upright. There were three birds walking across a sandy beach toward him. He blinked several times, trying to get his eyes to see them properly. He looked at the beak in his hand. It was proof that he really had been in the belly of a whale, that this was not all some strange and terrible enchantment. But what about his tongue? He had been dying of thirst, and now his tongue was back to its normal size.

Perchance he was dreaming. Because the birds coming his way were very large. They cleared the jumble of driftwood at the high tide line, and they had to be six feet tall. He dug the sharp point of the cuttlefish beak into the palm of his hand to wake himself up. But he did not wake. He only felt the pain he was causing himself.

Worse, he realized that all along the birds had been speaking as humans speak. They had the throaty voices of birds, but they formed words, the way a parrot does. But these were not parrots. And they were not simply repeating a human phrase over and over, they were talking.

They were a cormorant, a pelican, and a crow. The cormorant wore a pair of spectacles, pinched onto his bill in the manner of a scholar or a scribe. The pelican was perhaps the very one who had fed him a drop of blood.

The crow stepped up to him and looked him up and down with one black eye. He leaned in with his beak so close that the fisherman saw the flat feathers lift up over the crow’s nostrils when he sniffed at him.

The crow stepped back and looked at him with his other eye. He puffed out his chest feathers. He opened his beak to speak, and the rank smell of carrion filled the fisherman’s nose.

“You featherless piece of shite,” the crow said. “What brings you here?”

Insults from a talking bird—what manner of varlet was this? Ye gods, the fisherman thought, I must have sailed off the edge of the world. Or been swum there by the great whale.

The pelican cooed soothingly, as if to tell the fisherman that he was not entirely in agreement with the crow’s phrasing. The cormorant stretched his neck, making himself taller than the crow, and looked down on the black bird. His spectacles gave him the superior air of a barrister who has secretly bribed a judge. The crow paid him no mind.

“Where am I?” the fisherman said.

“You stink,” the crow said. “I thought you humans took baths now and again.”

All the birds were circling him, looking him up and down, first with one eye, then the other, the cormorant regarding him over the top of his spectacles. The pelican stopped in front of him. “Are you lost?” His long bill lay against his chest, and his yellow eye was not so unfriendly as the crow’s. “How do you come to be here?”

“We know how he got here,” the crow said, but before he could continue, the pelican turned and spread his wings, shielding the man from the crow. He shook his wide wings, rattling his feathers. “However he arrived here,” the pelican said, “this man is our guest.”

The crow scratched at the sand and uttered several harsh caws. “Guest, you say? Not my guest. He’s trouble, anybody can see that. Look at the mischief he’s already caused.”

“Mischief?” the fisherman said. “What mischief? I’ve only just got here.” He didn’t like these birds, especially the crow, whose black eyes regarded him as if he were nothing more than flotsam, and maybe worth a peck to test his flavor. The cormorant and the pelican had bills long enough to grab the fisherman by the throat and strangle him. His knife was gone, lost when he was swallowed by the whale. All he had to defend himself with was the cuttlefish beak, and they would rip him to pieces before he could do them much damage.

Perhaps he could distract them with flattery. “Friend crow, are you one of the gods of this place?”

“I’m no crow, you fool,” the crow said. “I am Raven, and I am the King of the Dead.”

“Imposter,” the cormorant said, “you are no raven.” The cormorant opened wide his hooked bill, ready to wring the crow’s neck, and the crow pulled away. “Swallow your pride,” the cormorant said to the crow. “It is not poison, you will not perish.”

“Oh, and I suppose you think you can be king here?” the crow said. He stalked around in a belligerent circle, muttering to himself, “All I ask is a little respect.”

Ye gods, what a tiresome bird, the fisherman thought. “Please,” he said, “I am a simple fisherman. Tell me where I am.”

The pelican turned back to the fisherman, his wingspan taking in the whole of the inlet as he swung from side to side. “This,” he said, “is the Isle of the Dead.”

At this the fisherman sank to his knees and bowed his head. The gods be praised, he had arrived at his destination. “At last,” he said. “I am here.”

The cormorant stretched his neck down, his head now below the fisherman’s, and tilted so the bird was looking up at him. “We don’t get many of your kind who are so happy to arrive.” His eye was a blue that put the fisherman in mind of his beloved’s eyes. But the cormorant’s eye was perfectly round, and his rapt gaze was unnerving. Staring into it made the fisherman feel queasy.

He stood again, and faced the three birds. “I have come for my beloved,” he said, “who has preceded me.”

“Aw,” they all said, their chuttering voices more birdlike than ever. “Aw, aw, aw.” They clucked and cooed and cawed at one another at some length in the lingua franca of birds, very like a flock of chickens who have discovered a wayward chick. From time to time they looked at the fisherman—the cormorant with curiosity, the pelican with pity, the crow with scorn. The crow ended their discussion with a series of caws, louder and louder, until the cormorant and the pelican were silent.

“This is an old story,” said the crow. “I suppose you want to take her back with you?”

Back? The fisherman had never considered the possibility. “All I want,” said he, “is to be with her for the rest of my days.”

The crow began clawing at the sand. “Naw, naw, naw,” the crow said. “We don’t allow that sort of thing here. You have no more days, you walking pile of whale scat. You’re dead.”

“He is not dead,” the pelican said. “I saved him from death.”

“Kiaww,” the crow said, “that was your mistake, not mine.”

“Prima facie, he did not come on the canoe with the others,” the cormorant said. “Ergo he is not dead.”

“Canoe?” the fisherman said. “What canoe?”

The cormorant and the pelican began to cluck each

to the other, the pelican saying such things as “He lives, he lives,” and the cormorant, for his part, muttering “Habeas corpus, autem non est mortuorum, et non sequitur, non habemus potestatem,” and other such barristical phrases.

The crow puffed up his chest feathers and spread his oily black wings. “Knock it off, aw aw aw aw!” he said. “Quiet!” The other two birds puffed up their chest feathers and spread their wings, and they were anything but quiet. They all three chanted and flapped in ripe cacophony, with the pelican, who was the shortest of the three, sometimes hopping from one foot to the other. All of them with their necks stretched up for added height, although this was of most benefit to the cormorant. They kept this fracas going for some time, and then, as if on some signal that only birds could see, they all stopped at once and turned to face the fisherman.

“Not an easy thing to do, finding your beloved,” said the crow. “There are so many here.”

Was that an overture to a bribe? The fisherman responded in kind. “I’ve come a long way to find her,” he said. “Surely there is a way?”

The crow went back to clawing in the sand, and he uncovered a clam. He flipped it over, and then he covered it back up. The pelican and the cormorant clucked in alarm at this, but the crow spoke, as if to cut them off. “Just how much is your beloved worth to you?” he said. The crow leaned in, the sharp tip of his beak a finger’s width away from the fisherman’s nose. “Your right eye?” the crow said. “Your left eye?” The fisherman wrinkled up his nose in disgust at the crow’s carrion breath. The crow gave him a hard look. “How about both eyes?” The fisherman stared right back at him. He was not going to let this foul-mouthed maggot-pie of a bird have the better of him.

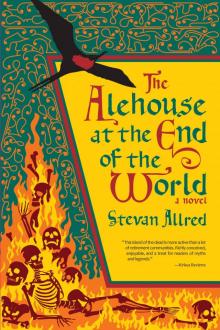

The Alehouse at the End of the World

The Alehouse at the End of the World